WWW.FAIRAMENDMENT.US

| NEWS |

Crime,

Realignment

and the

Will Rogers

Republican

By Karl Spence

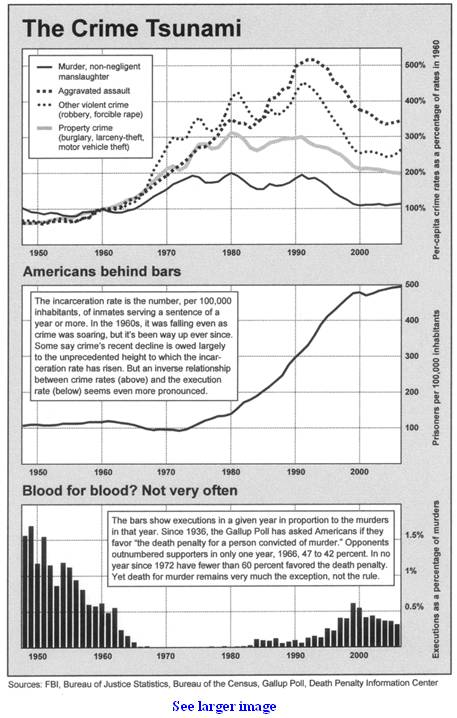

The great American crime wave we’ve been suffering these 40 years is far from over. When it finally does end, the phrase “Great Crime Wave” may well go into the history books alongside “Great Depression.” Why so? Because we’ve had it that bad. Between 1960 and 1991, the U.S. murder rate doubled. The rate of major crimes against property tripled. The rates of robbery and forcible rape more than quadrupled, and that of aggravated assault more than quintupled. Even after receding from its crest of the early ’90s, crime in the United States remains, per capita, more than twice what it was 50 years ago — and in recent years the mayhem has been increasing again. [1] In our time, crime has killed more Americans than died in World War II. Its toll dwarfs that of 9/11 — it even dwarfs that of the terrible Indian Ocean tsunami.

This

crime tsunami didn’t have to happen,

[2] nor does it need to continue.

The Great Crime Wave can be crushed. And the party that crushes it will rule

American politics for a generation or more, just as the Democrats did from the

reign of Franklin Roosevelt to the rise of Ronald Reagan.

This

crime tsunami didn’t have to happen,

[2] nor does it need to continue.

The Great Crime Wave can be crushed. And the party that crushes it will rule

American politics for a generation or more, just as the Democrats did from the

reign of Franklin Roosevelt to the rise of Ronald Reagan.

Republicans have had this opportunity staring them in the face for almost 40 years now, and they haven’t seized it yet. Richard Nixon won election in 1968 partly due to concern about crime in the streets, but as president he was no help. An unseemly bout of crime in the suites led to his resignation. His successor, Gerald Ford, had nothing urgent to say about crime. A month before Ford and Jimmy Carter faced the voters in 1976, an elderly South Bronx couple who had been robbed and tortured, twice, in their own apartment hanged themselves, leaving a note that said they didn’t want “to live in fear anymore.” [3] Neither candidate even noticed.

Then came Reagan. His election could have heralded the end of the Great Crime Wave, but it did not. Neither did Reagan usher in an era of single-party dominance. For all his achievements, he never gained complete victory over the evils that called him onto history’s stage. With FDR it was different. By the time Roosevelt died, both depression at home and fascism abroad were done for. But in the 1980s, while Reagan’s foreign and economic policies did indeed set the stage for victory in the Cold War and sparked an historic economic boom that overcame the “stagflation” of the Carter years, the sickeningly high crime rates that were a major part of the Carter malaise just took a deep breath and then climbed higher and higher. [4]

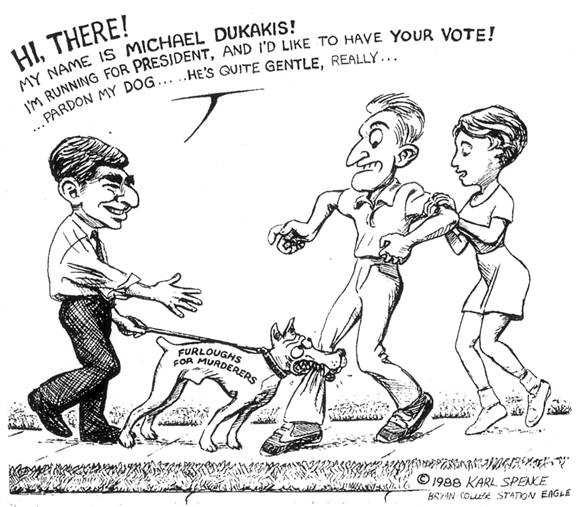

The only post-Reagan presidential election in which the GOP really mopped the floor with the Democrats — the 1988 matchup between George H.W. Bush and Michael Dukakis — is testimony to the people’s hunger for the return of law and order. Dukakis, whose line was that the election was not about ideology but about “competence,” was well ahead in the summer polls. But as Massachusetts governor, the oh-so-progressive Dukakis had repeatedly vetoed his Legislature’s attempts to enact a Supreme Court-compliant death penalty, and he was in the practice of commuting the sentences of murderers sentenced to “life imprisonment without parole.” He also pocket-vetoed a bill that would have barred first-degree murderers from participating in the state’s prison furlough program. The result was a new set of vicious crimes perpetrated by Willie Horton, a killer who would have been either put to death or locked up for good if not for Dukakis’s ministrations. When voters nationwide were made aware of this, Dukakis lost in a landslide. [5]

Unfortunately, no decisive action against crime flowed from that. Bush I, like Reagan before him, failed to stem the crime tsunami, and four years later, with violent crime at record levels, he was shown the door. Other issues contributed to that result, of course, but Bush’s victorious Democratic challenger took pains to distance himself from Dukakis’s arrant softness on crime, making a point of overseeing an execution in Arkansas early in the 1992 campaign. Had Bill Clinton not made clear he was no Dukakis, he could never have become president. [6]

With both parties at least making the right noises about it, crime did begin to fall in the 1990s, but that trend was driven by a resurgent death penalty, a huge increase in the number and length of incarcerations, and other factors unfolding at the local level that had nothing to do with policies set in the White House. And President Clinton’s judicial appointments have belied candidate Clinton’s anti-crime stance: Supreme Court Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer vote just as reliably to the left on the death penalty and other law enforcement issues as any Dukakis nominees would have done. [7]

Meanwhile, with the incarceration rate maxed out and the resurgence of executions stalled by unrelenting liberal litigation, violent crime has leveled off and is now starting a resurgence of its own, never having declined to anything near its low 1950s levels. (The sole exception to that is the murder rate, and its subsidence is owed mainly to advances in emergency medical care, not to any return of law and order. Murderous attacks whose victims survive are generally classified as aggravated assaults, and with more victims being saved in ER, the rate of aggravated assault remains more than three times what it was in 1960. Americans continue to suffer murderous attacks far more frequently than we did two generations ago.) [8]

The 1994 Republican congressional victory, like Clinton’s election, involved issues other than crime, and, though it coincided with the remission in the crime wave, it had no more to do with that than Clinton’s presidency did. Suppression of crime has never in all these years reached the top of the Washington agenda. Accordingly, the GOP’s “Contract with America” produced no true, FDR-style political realignment. Like Reagan’s election in 1980, it led not to solid Republican control but to yet more closely and bitterly divided government, an era of hard feelings that is likely to continue for years to come, until some signal event hands one party a decisive advantage and chastens the other into “me too” meekness.

So, now that the Republicans have had their heads handed to them in the 2006 election [make that two successive national elections — k.s., Nov. 5, 2008], they might wish to consider what a really hard, sustained and victorious anti-crime campaign might do for them. To see the possibilities, they need look no further than one of the most famous FDR Democrats of them all.

Will Rogers is a name perhaps only vaguely

familiar to younger Americans, but in his day he was bigger than Walter

Cronkite, Jay Leno, Tom Hanks, Rush Limbaugh and the Instapundit put together.

An Oklahoma Cherokee cowboy and wandering bronco-buster who got into show

business via the Wild West Show, he became one of the most loved and admired

Americans of all time, a top star on stage, screen and radio, the most widely

read humorist and news commentator of his era. When in 1935 a plane crash in

Alaska killed him, the news hit the country hard, causing what was called

the greatest outpouring of grief since the death of Abraham Lincoln.

[9] His most famous sayings are “I

never met a man I didn’t like,” “All I know is what I read in the papers,” and

“I am not a member of any organized political party. I am a Democrat.”

Will Rogers is a name perhaps only vaguely

familiar to younger Americans, but in his day he was bigger than Walter

Cronkite, Jay Leno, Tom Hanks, Rush Limbaugh and the Instapundit put together.

An Oklahoma Cherokee cowboy and wandering bronco-buster who got into show

business via the Wild West Show, he became one of the most loved and admired

Americans of all time, a top star on stage, screen and radio, the most widely

read humorist and news commentator of his era. When in 1935 a plane crash in

Alaska killed him, the news hit the country hard, causing what was called

the greatest outpouring of grief since the death of Abraham Lincoln.

[9] His most famous sayings are “I

never met a man I didn’t like,” “All I know is what I read in the papers,” and

“I am not a member of any organized political party. I am a Democrat.”

Rogers spoke at the Democrats’ convention in 1932 and welcomed Franklin Roosevelt to Southern California during the campaign. The “cowboy philosopher” became a cheerleader for the New Deal. He liked the idea of soaking the rich, favored big government programs to end the Great Depression, enjoyed needling big business, and was disgusted when FDR’s New Deal centerpiece, the National Recovery Administration, was ruled unconstitutional. His memory is claimed proudly today by Democrats and liberals of every stripe. When left-wing columnists such as Molly Ivins affect a “folksy” style, they are aping Rogers, whose folksiness came naturally. [10]

Yet on crime and related social issues, Rogers often said things you’d hear today only from a conservative Republican.

Rogers, an aviation enthusiast, was a friend of Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh, whose baby was kidnapped and murdered in 1932. He was a welcome guest at the Lindberghs’ home, and his ranch became a refuge for them after their child was slain. Rogers favored a mandatory death penalty for crimes like that, [11] and his humor often expressed the idea that criminals in this country don’t get the punishment they deserve. For example:

● “American murder procedure is about as follows: foul enough to commit a crime, dumb enough to get caught, smart enough to prove you was crazy when you committed it, and fortunate enough not to hang for it.”

● “There must not be such a thing in this country as an ‘amateur crook.’ Every person that is caught in some terrible crime, you find where he has been paroled, pardoned, and pampered by every jail or insane asylum in the country. Some of these criminals’ records sound like a tour of a one-night theatrical troop.”

● “Pardoning sure has been one industry that hasn’t been hit by recession.”

● “Robberies! Where they used to take your horse, and if they were caught, they got hung for it; now they take your car, and if they are caught, it’s a miracle, and they will perhaps have the inconvenience of having to go to court and explain.”

● “Is our court procedure broken down, lame, or limping? Something sure is cuckoo. It looks like after a person’s guilt in this country is established, why, then the battle as to whether he should be punished is the real test of the court. It seems if he is lucky enough to get convicted, or confesses, why he has a great chance of going free.”

● “Papers have been commenting on the novel way the state of Nevada executed a man for committing murder. The novelty of that was that a prisoner was executed in any way for just committing murder.”

● “Of course, the best way out of this crime wave would be to punish the criminals, but, of course, that is out of the question! That’s barbarous, and takes us back, as the hysterics say, to the days before civilization.” [12]

Hysterics to the contrary, Rogers’ view of crime

and punishment is in fact shared by many of the heroes of civilization. For

example, St. Paul said government “does not bear the sword in vain” but is

appointed by God “to execute his wrath on the wrongdoer.”

[13] St. Augustine saw “the death penalty of the judge” and “the

barbed hooks of the executioner” as necessary social institutions, for “while

these are feared, the wicked are kept within bounds and the good live more

peacefully among the wicked.”

[14] Erasmus contrasted God’s potential forgiveness of sins in the

hereafter with the duty of temporal rulers on earth, noting that were a king to

forgive murder as God can do, “then the people would cry that the king’s

clemency was inordinate, since it impaired the force of the law and encouraged

sin by the impunity it allowed.” [15]

Martin Luther affirmed that Christ’s warning to Peter at

Gethsemane (“All who take the sword will perish with the sword”) is no

preachment of pacifism but rather a prescription of punishment, “to be

understood in the same sense as Genesis 9:6 (‘Whoever sheds man’s blood, by man

shall his blood be shed’). There is no doubt that Christ is here invoking those

words, and wishes to have this commandment introduced and confirmed [in the New

Covenant].”

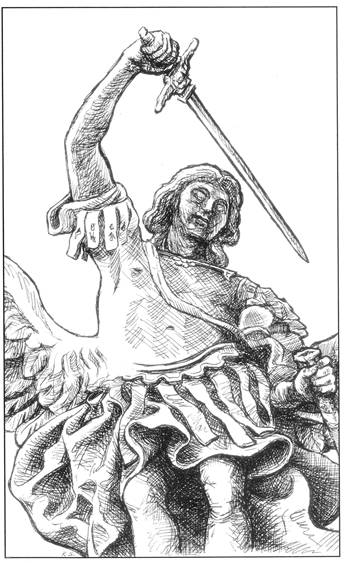

[16] John Calvin wrote: “The true justice, then, is to

pursue the evildoers and the unrighteous with drawn sword. If [rulers] sheath

their sword and keep their hands unsullied by blood, while the wicked roam about

massacring and slaughtering, then so far from reaping praise for their goodness

and justice, they make themselves guilty of the greatest possible injustice.”

[17]

Hysterics to the contrary, Rogers’ view of crime

and punishment is in fact shared by many of the heroes of civilization. For

example, St. Paul said government “does not bear the sword in vain” but is

appointed by God “to execute his wrath on the wrongdoer.”

[13] St. Augustine saw “the death penalty of the judge” and “the

barbed hooks of the executioner” as necessary social institutions, for “while

these are feared, the wicked are kept within bounds and the good live more

peacefully among the wicked.”

[14] Erasmus contrasted God’s potential forgiveness of sins in the

hereafter with the duty of temporal rulers on earth, noting that were a king to

forgive murder as God can do, “then the people would cry that the king’s

clemency was inordinate, since it impaired the force of the law and encouraged

sin by the impunity it allowed.” [15]

Martin Luther affirmed that Christ’s warning to Peter at

Gethsemane (“All who take the sword will perish with the sword”) is no

preachment of pacifism but rather a prescription of punishment, “to be

understood in the same sense as Genesis 9:6 (‘Whoever sheds man’s blood, by man

shall his blood be shed’). There is no doubt that Christ is here invoking those

words, and wishes to have this commandment introduced and confirmed [in the New

Covenant].”

[16] John Calvin wrote: “The true justice, then, is to

pursue the evildoers and the unrighteous with drawn sword. If [rulers] sheath

their sword and keep their hands unsullied by blood, while the wicked roam about

massacring and slaughtering, then so far from reaping praise for their goodness

and justice, they make themselves guilty of the greatest possible injustice.”

[17]

Henry Fielding, the great 18th century English novelist and jurist, argued that

clemency to criminals is cruelty to their victims. “To desire to save these

wolves in society may arise from benevolence,” he said, “but it must be the

benevolence of a child or a fool, who, from want of sufficient reason, mistakes

the true objects of his passion, as a child doth when a bug-bear appears to him

to be the object of fear.” Describing the havoc inflicted by violent predators

upon the innocent, he said: “Let the good-natured man, who hath any

understanding, place this picture before his eyes, and then see what figure in

it will be the object of his compassion.”

[18] President Lincoln in his Second Inaugural eloquently affirmed the justice of

paying blood for blood, and, like Fielding, he himself sent many men to the

gallows.

[19]

And C.S. Lewis held it “perfectly right for a Christian

judge to sentence a man to death”; he observed that “if one had committed a

murder, the right Christian thing to do would be to give yourself up to the

police and be hanged.”

[20]

Henry Fielding, the great 18th century English novelist and jurist, argued that

clemency to criminals is cruelty to their victims. “To desire to save these

wolves in society may arise from benevolence,” he said, “but it must be the

benevolence of a child or a fool, who, from want of sufficient reason, mistakes

the true objects of his passion, as a child doth when a bug-bear appears to him

to be the object of fear.” Describing the havoc inflicted by violent predators

upon the innocent, he said: “Let the good-natured man, who hath any

understanding, place this picture before his eyes, and then see what figure in

it will be the object of his compassion.”

[18] President Lincoln in his Second Inaugural eloquently affirmed the justice of

paying blood for blood, and, like Fielding, he himself sent many men to the

gallows.

[19]

And C.S. Lewis held it “perfectly right for a Christian

judge to sentence a man to death”; he observed that “if one had committed a

murder, the right Christian thing to do would be to give yourself up to the

police and be hanged.”

[20]

Capital punishment, furthermore, was endorsed by the authors of the U.S. Bill of Rights. Having approved the Eight Amendment’s ban on “cruel and unusual punishments” (i.e., no drawing and quartering, no boiling in oil, etc.), the First Congress proceeded to enact a law prescribing the hangman’s noose for murderers, rapists, robbers and counterfeiters. [21]

Rogers’ readiness to “punish the criminals” also happens to be shared by about two-thirds of the American people, who have for decades been telling pollsters that they favor the death penalty for murder. [22] And his expectation that such punishment would get us “out of this crime wave” is bolstered not just by common sense, but by the results of social science research.

It may come as news to most people, but many studies have found that the death penalty does have a deterrent effect when executions are actually carried out. The first such study, by New York economist Isaac Ehrlich in 1975, estimated eight murders deterred for each murderer put to death. In 1986, North Carolina’s Stephen K. Layson put it at 18 — a result duplicated recently in a much-ignored Emory University study by Hashem Dezhbakhsh, Paul H. Rubin and Joanna M. Shepherd. Other researchers, including Zhiqiang Liu, Walter Vandaele, Kenneth Wolpin, Llad Phillips, Subhash Ray, H. Naci Mocan, R. Kaj Gittings, Dale Cloninger, Roberto Marchesini and George Brower, have found similar results, using, as Brower put it, “a variety of methods and data from several countries.” [23]

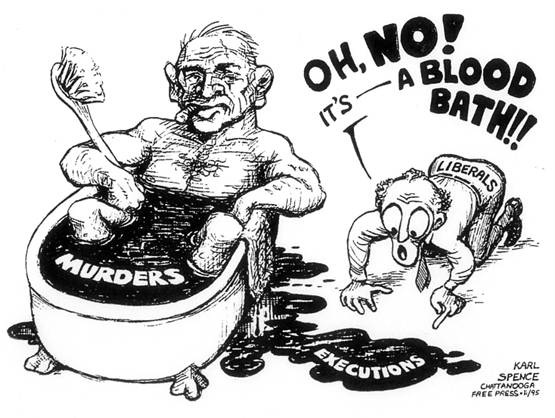

But none of that matters. The hysterics, as

Rogers called them, have the ear of the Supreme Court, and under its rulings

capital punishment is hardly ever enforced. In the past 40 years, murderers have

killed more than 760,000 Americans, and just over 1,000 of them have paid for

their crimes with their lives. In other words, capital punishment’s opponents

get their way nearly 99.9 percent of the time.

But none of that matters. The hysterics, as

Rogers called them, have the ear of the Supreme Court, and under its rulings

capital punishment is hardly ever enforced. In the past 40 years, murderers have

killed more than 760,000 Americans, and just over 1,000 of them have paid for

their crimes with their lives. In other words, capital punishment’s opponents

get their way nearly 99.9 percent of the time.

And it should come as no surprise that with the hysterics in charge of things, the crime wave of Rogers’ day (personified by Al Capone, John Dillinger, and Bonnie and Clyde) has been eclipsed. As Atlantic Monthly writer Eric Schlosser put it, Americans in this generation have been suffering “the carnage of a shadowy, undeclared civil war” — one leaving in dead and wounded “more casualties than the U.S. military has suffered in all the wars of the past 200 years.” [24]

To bring this civil war to an end, we will need to upset the hysterics in more ways than one. Look again at the 1950s. Among hysterics — pardon me, among “progressives” — it’s an infamous decade, a white-bread era of “McCarthyism” and “conformity.” But what about crime? The rate of executions back then was not all that much higher than it is now, and the incarceration rate was much, much lower. Yet crime was less than half of what we today are expected to accept as normal. Clearly, the ’50s had more going for them than two-toned Chevys and blue suede shoes. James Q. Wilson’s observation, though made in reference to an earlier era, applies to this one as well: “One can imagine living in a society in which the shared values of the people, reinforced by the operation of religious, educational, and communal organizations concerned with character formation, would produce a citizenry less criminal than ours is now without diminishing to any significant degree the political liberties we cherish. Indeed, we can do more than imagine it; we can recall it.” [25]

Crime will get back to where it once belonged, then, when we take effective measures not only to punish the criminals but also to steer their younger brothers and sisters away from the culture of crime, to instill in them a respect for authority and a desire for righteousness. And Will Rogers had some surprising things to say about that, too.

While not a great churchgoer or a proselytizer for any one sect, Rogers gave generously to churches, synagogues, the Salvation Army and other religious groups. He spoke of Jesus as “Our Savior” and recommended the Ten Commandments as holding good “for all men.” Referring to the main religious dispute of his day, he wrote: “If there are people who think they come from a monkey, it’s not our business to rob them of what little pleasure they may get out of imagining it. What good will it do at this late date to argue over who we came from. The Lord didn’t leave any room for doubt when He told you how you should act when you got here. His example and the Commandments are plain enough. So let’s just start from there.” [26]

So far, so conventional. But Rogers’ dissent from irreligion went much further than what some might dismiss as, for the time, rather routine expressions of piety. In 1927, he returned from a visit to the Soviet Union sounding very much like a member of the Religious Right.

Other Westerners had been shown around that Mecca of the Left and come back all starry-eyed. Rogers was given the same Potemkin tour, but somehow he wasn’t taken in. “What has all these millions of innocent, peace-loving people done that through no fault of their own they should be thrown into a mess like this?” he asked. And he zeroed in on what he considered to be the crucial point:

“The Russians … are at heart just big, simple, kind-hearted, God-fearing people. … [But] the basic foundation of the Communist Party is to be a nonbeliever. They try to lead all these Russians to believe that all their troubles all these years have been directly traceable to their religion. … Course, you have to admit that fanatical religion driven to a certain point is almost as bad as none at all, but not quite. Now they will tell you that the worship of Leninism is their religion. Lenin preached Revolution, Blood and Murder in everything I ever read of his. Now they may dig ’em up a religion out of that, but … I don’t think anyone that just made a business of proposing [it] for a steady diet would be the one to pray to and try and live like. …

“If the Bolsheviks say that religion was holding the people back from progress, why, let it hold them back. Progress ain’t selling that high. If it is, it ain’t worth it. … They picked the only one thing I know of to suppress that is absolutely necessary to run a Country on, and that is Religion.” [27]

Here again is a point on which Rogers agrees

with our nation’s Founding Fathers, including the authors of the Bill of Rights.

Here again is a point on which Rogers agrees

with our nation’s Founding Fathers, including the authors of the Bill of Rights.

The First Congress, having approved the First Amendment’s ban on a federal “establishment of religion,” went on to renew the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which cites the promotion of “religion, morality, and knowledge” as among the purposes of public education. [28] George Washington in his Farewell Address called religion and morality “indispensable supports” to “the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity.” John Adams likewise wrote, “Our Constitution was made only for a religious and moral people. It is wholly inadequate for the government of any other.” [29] And even the “wall of separation” man himself, Thomas Jefferson, held similar views. Concerning “that branch of religion which regards the moralities of life and the duties of a social being,” he professed to be as orthodox as any churchman. Jefferson repudiated “the anti-Christian system imputed to me by those who know nothing of my opinions.” He wrote: “The practice of morality being necessary for the well-being of society, [God] has taken care to impress its precepts so indelibly on our hearts that they shall not be effaced by the subtleties of our brain. We all agree in the obligation of the moral precepts of Jesus, and nowhere will they be found delivered in greater purity than in his discourses.” [30]

Other heroes of American history, ranging from Theodore Roosevelt [31] to Harry Truman, [32] have spoken in a similar vein, which is a far cry from the line pushed by today’s secular liberals. Leftist hostility toward the Ten Commandments, the Pledge of Allegiance, the grade-school Christmas pageant, the courthouse crèche, the pre-game football prayer, etc., has never been shared by most Americans. Yet it’s the Left, through its influence on the courts, that holds the reins today. Regardless of what politicians may promise, the free expression of public piety, like the restoration of law and order, remains remote from present possibilities.

Millions of Americans yearn for something more. These Will Rogers Democrats are not small-government conservatives. They rather like the services proffered by a nanny-state Uncle Sam. But they long to live in a society that is free of wanton criminal violence. They want their children’s education and peer-group culture to promote, not subvert, what Jefferson called “the moralities of life and the duties of a social being.” And they are fed up with the Atheist Crank Litigation Union’s unrelenting war against all things holy.

What would it take to turn the Will Rogers Democrat into a Will Rogers Republican? It will take action, not talk. And that means taking on the Supreme Court of the United States.

Here is where the GOP has fallen way short. The

changes that transformed Will Rogers’ America into Willie Horton’s America were

largely driven by judicial activism — the interpretation of the Constitution, on

points where its original meaning is clear, in a sense deliberately contrary to

that meaning so as to obtain a political result favored by the Court. Such

activism was viewed by the Constitution’s Framers as illegitimate, a judicial

usurpation of legislative power.

[33] In The Federalist

Papers, it’s called grounds for impeachment.

[34] Even

Chief Justice John Marshall, supposedly the grandfather of judicial activism,

emphatically disavowed it.

[35] But from the time of Nixon

onward, the Republican response to judicial activism has been merely to promise

the appointment of right-thinking justices who, it is hoped, will reverse the

activist rulings, or maybe qualify them or trim them in some way, or at least

not inflict more and more of them on us as time goes by. That approach, it

should be obvious by now, is too slow, too passive and too uncertain to do any

good. It amounts merely to wishful thinking. It hardly even rises to the level

of talk.

Here is where the GOP has fallen way short. The

changes that transformed Will Rogers’ America into Willie Horton’s America were

largely driven by judicial activism — the interpretation of the Constitution, on

points where its original meaning is clear, in a sense deliberately contrary to

that meaning so as to obtain a political result favored by the Court. Such

activism was viewed by the Constitution’s Framers as illegitimate, a judicial

usurpation of legislative power.

[33] In The Federalist

Papers, it’s called grounds for impeachment.

[34] Even

Chief Justice John Marshall, supposedly the grandfather of judicial activism,

emphatically disavowed it.

[35] But from the time of Nixon

onward, the Republican response to judicial activism has been merely to promise

the appointment of right-thinking justices who, it is hoped, will reverse the

activist rulings, or maybe qualify them or trim them in some way, or at least

not inflict more and more of them on us as time goes by. That approach, it

should be obvious by now, is too slow, too passive and too uncertain to do any

good. It amounts merely to wishful thinking. It hardly even rises to the level

of talk.

Not only has a reliance solely on judicial appointments yielded numerous disappointments (Harry Blackmun, John Paul Stevens and David Souter being only the worst examples), but even if it hadn’t it would miss the point. Let the federal bench be filled with Antonin Scalias — so long as justices are free to rule any way they please, ours will remain a government not of laws but of men. The meaning of the Constitution will continue to depend on the composition of the Court.

Judicial confirmation hearings have been called “the only conceivable occasion for a national debate over Constitutional jurisprudence.” [36] But opponents of judicial activism have found themselves at a disadvantage even during those hearings. The nominee says something vague and theoretical about not legislating from the bench, while his inquisitors (as Ted Kennedy did with Robert Bork) tell hair-raising tales of the horrors that might ensue were judicial activism’s less controversial effects to disappear. The watching public never gets reminded of the many real and present evils that judicial activism has unleashed upon us. While the millions of Americans who are complicit in abortion are enlisted in support of the activist side, the millions of us who have been victimized by violent crime are offered no prospect of relief and are given no reason to care about the nominee’s fate. And the activists themselves remain unmoved, their rulings untouched by anything their opponents have said or done.

Some of us, therefore, have been casting about for new ways to curb our imperial judiciary. In 1996, for example, Bork himself proposed making Supreme Court decisions reversible by a congressional majority vote. “If constitutional jurisprudence remained a mess,” he wrote, “at least it would be a mess arrived at democratically.” [37] But his proposal would have made the entire Constitution of no more force than any act of Congress. The idea went nowhere.

In 1997, Congressman Tom DeLay, who was then the House Majority Whip, called for impeaching some of the federal courts’ “particularly egregious” autocrats. That resulted only in a cascade of abuse against DeLay. He was denounced as a demagogic, ignorant, arrogant yahoo and compared to the extremist John Birch Society, which used to dot the countryside with “Impeach Earl Warren” billboards. [38]

Others, meanwhile, have proposed various status quo ante constitutional amendments: one to ban flag-burning, another to ban abortion, still more to ban same-sex marriage. At the federal level, none of those amendments has succeeded; they’ve all been checked by the idea that adopting them would be tampering with the Bill of Rights. On such occasions, it seems not one American in a hundred manages to recall that the judicial activism those amendments seek to counteract has itself tampered with the Constitution. Not one in a thousand has any idea that such tampering was categorically denounced by the very men who gave us that document.

I think there is a way to educate people about that, through an amendment, based on the Framers’ precepts, that would make those precepts binding on today’s justices. What Marshall called “a fair construction” of the Constitution — one “which gives to language the sense in which it is used, and interprets an instrument according to its true intention” [39] — is in today’s legal world merely a theory in dispute. It’s variously called “strict construction,” or “interpretivism,” or “originalism,” and it’s dismissed by the liberal elite as “out of the mainstream.” A Fair Construction Amendment would make originalism a positive requirement, by instructing the justices to take the Constitution’s original meaning, “the sense in which it was accepted and ratified by the nation,” as their guide. This would restore Americans’ ability to determine policy on a whole array of issues in which we have more in common with the Framers than with today’s judicial mandarins. It would not leave us wishing and a-hoping that some future Supreme Court majority might kindly return to us our right of self-government. Rather, it would enable us to reclaim the powers a usurping Court has taken away from us.

The amendment would need to obviate Ted Kennedy’s horror stories by ratifying those court-imposed changes — the overthrow of Jim Crow segregation, for example — that we should have made for ourselves. But everything else would be ours again. We’d be free to provide for school prayer and to control pornography, to regulate abortion as we see fit, to have done with reverse discrimination, “gay rights” and the perennial anti-Christmas lawsuits. Most crucially for crime victims, we’d be free to set severe penalties for violent crimes and see those penalties carried out. At long last, the end of the Great Crime Wave would be within our grasp.

In the wake of the 2006 GOP rout, The American Spectator published a symposium in which leading conservative thinkers considered the Republican Party’s next move. They talked about taxes and earmarks and entitlements and “the growth of government,” and they prescribed a return to small-government conservative principles. None of their essays mentioned crime. [40] Meanwhile, a Washington Post column by historian Douglas Brinkley looked toward lame duck George W.’s place in history. Bush II will likely be ranked alongside Herbert Hoover, Brinkley thinks, as a failed president. That is mainly because of the ill-starred war in Iraq, in which several thousand American soldiers have died — needlessly, Brinkley thinks. [41]

In the Great Crime Wave, several hundred thousand Americans have died — needlessly, I believe. We have only to prove those deaths were needless, by taking the actions which can turn the crime wave off like a light. Once people find that most of the murder and mayhem we’ve endured for so long was no inevitable effect of forces beyond our control but instead was enabled, sheltered and even incited by liberal dogmas, then and only then will the Will Rogers Democrat become a Will Rogers Republican. And then it will be the crime-coddling hysterics, not Bush, who will be hustled off to Hooverville.

Karl Spence is the author of Yo! Liberals! You Call This Progress?, from which parts of this essay were drawn. Yo! Liberals! is available at Amazon.com or directly from Fielding Press. More information about the Fair Construction Amendment is available here and here.

Beaumont Enterprise photo by Pete Churton

Kim Durman holds a picture of twin sister Kathleen while her sister Sherra and friend Kristina Munoz hold a poster they planned put up at a mall in Beaumont, Texas, in 1993. Kathleen had been murdered 10 years before, and the women were trying to persuade the Texas parole board not to release her killer. [42]

Notes

[1] See chart. Crime figures are from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports, including its preliminary report for 2006. That report confirms figures compiled by the Police Executive Research Forum, which indicate that the upturn in violent crime that began in 2005 was continuing, even accelerating, in 2006. ——— Kevin Johnson, “Dozens of cities see jump in murders, robberies,” USA Today, Oct. 12, 2006; “Chief Concerns: A Gathering Storm — Violent Crime in America,” October 2006, accessible online at www.policeforum.org/upload/Gathering-Storm-PRINT-Final_110473745_ 1027200610304.pdf [back]

[2]

Those who want some no-fault explanation for the crime wave have pointed to the

passage of the baby boomers through young adulthood. But much more than that was

at work. In 1960, “crime-prone”

young adults comprised 8.9 percent of the population and accounted for 18

percent of arrests; in 1980, they peaked at 13.3 percent of the population and

accounted for 35 percent of arrests. The 18-24 age bracket had doubled its share

of arrests while its share of the population increased only by half — an

increase in youthful criminality which, though it may be the fault of young

people’s upbringing in the 1960s and ’70s, cannot be blamed on their mere

existence. Nor can the surge in young adults explain the fact that other age

groups were becoming more lawless as well. Had there been no changes in American

society other than the baby boom’s “pig in the python” movement through the age

brackets, then one would expect, based on the 1960 arrest percentages, an

increase in crime due solely to age shift of 10 percent — a tiny fraction of the

actual increase.

Percent of population

Percent of arrests

Age 1960

1980

Age 1960 1980

< 17

35.7 28.1

< 17 14

22

18-24

8.9 13.3

18-24 18

35

25-44 2 6.1

27.7

25-44 43

34

45 +

29.2 30.9

45 + 25

9

Percentage of arrests in 1960 times percentage of population in 1980 divided by

percentage of population in 1960

< 17 14 x 28.1 /

35.7 = 11.0

18-24 18 x 13.3 /

8.9 = 26.9

25-44 43 x 27.7 / 26.1

= 45.6

45 + 25 x 30.9 /

29.2 = 26.5

—–——

Expected crime rate in 1980 as a percentage of 1960 rate:

110.0

Data are from the Census Bureau and from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports.

Criminologist James Q. Wilson, a prominent dissenter among the academics who sought to explain the crime wave, has stated flatly: “Age shift could not by itself have produced the crime increases of the 1960s and 1970s.” ——— “Crime and American Culture,” The Public Interest, Winter 1983, p. 36. See also Steven D. Levitt, “The Limited Role of Changing Age Structure in Explaining Aggregate Crime Rates,” Criminology, August 1999 (Volume 37, Issue 3), pp. 581-598. [back]

[3] “Couple, Recently Robbed, Take Their Own Lives, Citing Fear,” The New York Times, Oct. 7, 1976, p. A-51; Leslie Maitland, “Elderly South Bronx Couple Disregarded Advice to Move,” The New York Times, Oct. 8, 1976, p. D-15. [back]

[4] See chart. Reagan’s re-election campaign in 1984 proclaimed it was “Morning in America,” and, so far as crime trends in his first term were concerned, that seemed so. But it was a false dawn. Crime surged again and ended the decade higher than ever. [back]

[5]

Robert James Bidinotto, “Getting Away With Murder,” Reader’s Digest, July 1988,

pp. 57-63; Jack E. White, “Bush’s Most Valuable Player,” Time, Nov. 14, 1988,

pp. 20-21.

[back]

[5]

Robert James Bidinotto, “Getting Away With Murder,” Reader’s Digest, July 1988,

pp. 57-63; Jack E. White, “Bush’s Most Valuable Player,” Time, Nov. 14, 1988,

pp. 20-21.

[back]

[6] “On the national stage, something happened that would cement Clinton's support for the death penalty for years to come. Asked during the 1988 debates if Michael Dukakis would support the death penalty if his wife Kitty were raped and murdered, Dukakis stared into the camera, squinted into the lights above, and then said, ‘I think there are better and more effective ways to deal with violent crime.’ The answer ruined Dukakis. Bush relentlessly charged Dukakis with being soft on crime, and his loss changed the landscape of what Democrats could say about the death penalty.” ——— Alexander Nguyen, “Bill Clinton's Death Penalty Waffle — and Why It's Good News for Execution's Foes,” The American Prospect online, July 14, 2000. www.prospect.org/webfeatures/2000/07/nguyen-a-07-14.html [back]

[7] Most recently, Breyer and Ginsburg dissented from a 5-4 decision that reinstated the death sentence of a man who beat a young woman to death when she caught him burglarizing her home. Along with their liberal colleagues John Paul Stevens and David Souter, the two Clinton appointees voted to spare Fernando Belmontes’ life more than 25 years after he crushed 19-year-old Steacy McConnell’s skull with an iron dumbbell. Commenting on this, columnist George F. Will asks: “How did capital punishment jurisprudence reach its current baroque condition, in which cases live longer than did the murder victims?” ——— Bob Egelko, “Justices reinstate man's death sentence; Judge didn't stop jury from weighing good behavior, ruling says,” San Francisco Chronicle, Nov. 14, 2006, p. B3; Will, “Circuit Breaker: The High Court vs. Death Penalty Foolishness,” The Washington Post, Nov. 16, 2006, p. A27. [back]

[8] In 2002, researchers at Harvard Medical School and the University of Massachusetts at Amherst calculated, in AP’s words, that “without medical advances, 45,000 to 70,000 homicides would have been recorded annually nationwide” — more than three times what we’ve suffered with those advances. ——— “Massachusetts researchers cite medical care advances in decline in murder rate,” Associated Press dispatch, Aug. 11, 2002. [back]

[9] “The Story of Will Rogers,” an NBC News documentary produced in 1961 by Donald B. Hyatt, written by Richard Hanser and Rod Reed. [back]

[10] When Roosevelt was inaugurated, Rogers said: “America hasn’t been as happy in three years as they are today. No money, no banks, no work, no nothing, but they know they got a man in there who is wise to Congress, wise to our so-called big men. The whole country is with him, just so he does something. If he burned down the Capitol, we would cheer and say, ‘Well, we at least got a fire started anyhow.’ ” Seven months later, Rogers said, “I will say one thing for this Administration. It’s the only time when the fellow with money is worrying more than the one without it.” And in April 1935, Rogers mocked those who wondered where all the money was coming from for FDR’s “orgy of spending.” He hazarded a guess that the money was coming from “those that got it,” and asserted that “there’s just as much money in the country as there ever was, only fewer people have it.” No economic conservative he, nor economist either. ——— The Editors of Time-Life Books, This Fabulous Century (New York: Time-Life Books, 1969), v. IV, pp. 122-123; “The Voice of Will Rogers,” a phonograph album released in 1973 by the American Heritage Publishing Company in cooperation with the Will Rogers Memorial in Claremore, Okla.; Richard M. Ketchum, Will Rogers: His Life and Times (New York: American Heritage, 1973), pp. 323-329. [back]

[11] Bryan B. Sterling, The Best of Will Rogers (New York: Crown, 1969), p. 89. [back]

[12] Ibid., pp. 90-93. Such comments have an edge to them that wasn’t always present in Rogers’ humor. For example, this bit from one of his Ziegfeld Follies routines is pure flippancy: “Never a day passes in New York without some innocent bystander being shot. You just stand around this town long enough and be innocent, and somebody’s going to shoot you. One day there was four shot. That’s the best shooting ever done in this town. It’s hard to find four innocent people in New York, even if you don’t stop to shoot ’em. That’s why policemen never have to aim here. He just shoots up the street, anywhere. No matter who he hits, it’s the right one.” ——— “The Voice of Will Rogers." [back]

[13] Romans 13:3-4. [back]

[14] Corpus Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum, XLIV, 413-414, LXIII, 155, quoted by Herbert A. Deane in The Political and Social Ideas of St. Augustine (New York: Columbia University Press, 1963), pp. 138-139, 141-142.“ [back]

[15] Concerning the Immense Mercy of God” (1524), The Essential Erasmus, ed. John P. Dolan (New York: Mentor, 1964), pp. 231-235, 240-242. [back]

[16]

Luther commented further: “If all in the world were

true Christians, that is, if everyone truly believed, there would be neither

need nor use for princes, kings, lords, the Sword or law. What would there be

for them to do? Seeing that [true Christians] have the Holy Spirit in their

hearts, which teaches and moves them to love everyone, wrong no one, and suffer

wrongs gladly, even unto death. … A man would have to be an idiot to write a

book of laws for an apple-tree telling it to bear apples and not thorns, seeing

that the apple-tree will do it naturally and far better than any laws or

teaching can prescribe. … But since no man is by nature a Christian or just, but

all are sinners and evil, God hinders them all, by means of the law, from doing

as they please and expressing their wickedness outwardly in actions.

[16]

Luther commented further: “If all in the world were

true Christians, that is, if everyone truly believed, there would be neither

need nor use for princes, kings, lords, the Sword or law. What would there be

for them to do? Seeing that [true Christians] have the Holy Spirit in their

hearts, which teaches and moves them to love everyone, wrong no one, and suffer

wrongs gladly, even unto death. … A man would have to be an idiot to write a

book of laws for an apple-tree telling it to bear apples and not thorns, seeing

that the apple-tree will do it naturally and far better than any laws or

teaching can prescribe. … But since no man is by nature a Christian or just, but

all are sinners and evil, God hinders them all, by means of the law, from doing

as they please and expressing their wickedness outwardly in actions.

“If someone wanted to have the world ruled according to the Gospel, and to abolish all secular law and the Sword, on the ground that all are baptized and Christians and that the Gospel will have no law or sword used among Christians, who have no need of them, what do you imagine the effect would be? He would let loose the wild animals from their bonds and chains, and let them maul and tear everyone to pieces, saying all the while that really they are just fine, tame, gentle things. But my wounds would tell me different. … Before you rule the world in the Christian and Gospel manner, be sure to fill it with true Christians. And that you will never do, because the world and the many are un-Christian and will remain so, whether they are made up of baptized and nominal Christians or not.”

Luther concluded: “How the secular Sword and law are to be employed according to God’s will is thus clear and certain enough: to punish the wicked and protect the just.” And he wrote that while true Christians don’t need the sword for themselves, they submit to it and even wield it for the sake of others: “The Sword is indispensable for the whole world, to preserve peace, punish sin, and restrain the wicked. And therefore Christians readily submit themselves to be governed by the Sword, they pay taxes, honour those in authority, serve and help them, and do what they can to uphold their power, so that they may continue their work, and that honour and fear of authority may be maintained. … And therefore if you see that there is a lack of hangmen, court officials, judges, lords or princes, and you find that you have the necessary skills, then you should offer your services and seek office, so that authority, which is so greatly needed, will never come to be held in contempt, become powerless, or perish. The world cannot get by without it.” ——— “Von Weltlicher Oberkeit,” Luther and Calvin on Secular Authority, ed. Harro Hopfl (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991), pp. 7-15. [back]

[17] “On Civil Government” (Book IV, Chapter 20 of Institutio Christianae Religionis), Hopfl, op. cit., pp. 60-62. [back]

[18] Fielding, best known as the author of Tom Jones, actually took a harder line against crime than virtually anyone engaging the issue today. English law in Fielding’s time imposed death on mere thieves, and he urged that the law be enforced in its full rigor. The “certainty of destruction,” he argued, is essential to deterrence. Criminals “will derive more encouragement from one pardon than diffidence from twenty executions. … If therefore the terror of this example is removed (as it certainly is by frequent pardons) the design of the law is rendered totally ineffectual; the lives of the persons executed are thrown away, and sacrificed rather to the vengeance than to the good of the public, which receives no other advantage than by getting rid of a thief, whose place will immediately be supplied by another.” Few Americans would countenance “getting rid of a thief” by hanging him now, of course. But Fielding’s argument has an obvious application to the debate over capital punishment’s potential value in fighting more serious offenses. ——— Fielding, An Enquiry into the Causes of the Late Increase of Robbers (1751), ed. Malvin R. Zirker (Oxford: Clarendon, 1988), pp. 156-157, 165-166. [back]

[19]

“Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this

mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue

until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s 250 years of unrequited toil shall

be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by

another drawn with the sword, as was said 3,000 years ago, so still it must be

said: ‘The judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.’ ” Those

words are counted as among the finest in our heritage. Yet they embrace three

concepts much sneered at in liberal circles today: that justice requires

retribution, that ancient Scriptures are relevant to modern issues, and that our

country, along with all others, is subject to God’s authority.

[19]

“Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this

mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue

until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s 250 years of unrequited toil shall

be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by

another drawn with the sword, as was said 3,000 years ago, so still it must be

said: ‘The judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.’ ” Those

words are counted as among the finest in our heritage. Yet they embrace three

concepts much sneered at in liberal circles today: that justice requires

retribution, that ancient Scriptures are relevant to modern issues, and that our

country, along with all others, is subject to God’s authority.

Quite a few federal prisoners were executed during Lincoln’s presidency. Notable among them were 38 Santee Sioux who had murdered settlers during an uprising in Minnesota. Originally, 303 warriors had been sentenced to die, but Lincoln — anxious, he said, “not to act with so much clemency as to encourage another outbreak on the one hand, nor with so much severity as to be real cruelty on the other” — commuted the sentences of all but those who had “been proved of violating females” or had “participated in massacres, as distinguished from participation in battles.” The 38 were hanged at Lincoln's order the day after Christmas, 1862, at Mankato, Minn. It remains the largest mass execution in American history. ——— Abraham Lincoln, Speeches and Writings, 1859-1865, pp. 416-417; Mark E. Neely Jr., The Abraham Lincoln Encyclopedia, p. 161; The Editors of American Heritage, American Heritage Book of Indians, p. 344; Shelby Foote, The Civil War, A Narrative: Red River to Appomattox, p. 725. [back]

[20] Lewis also wrote: “It is no good quoting ‘Thou shalt not kill.’ There are two Greek words: the ordinary word to kill and the word to murder. And when Christ quotes that commandment, He uses the murder one in all three accounts, Matthew, Mark and Luke. And I am told there is the same distinction in Hebrew. All killing is not murder any more than all sexual intercourse is adultery.” ——— Mere Christianity (New York: Macmillan paperback, 1960), pp. 106-107. [back]

[21] Raoul Berger, Death Penalties: The Supreme Court’s Obstacle Course (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1982), pp. 47, 148-149. [back]

[22] Support in the Gallup Poll for “the death penalty for a person convicted of murder” has been solid since the ’70s. It peaked in 1994 at 80 percent; for the last several years, it has hovered around 69 percent. The ABC News / Washington Post poll, meanwhile, has averaged 67 percent support since 1996, and the Fox News / Opinion Dynamics poll has averaged 70 percent support since 1997. ———www.clarkprosecutor.org/html/death/opinion.htm [back]

[23] Robert Bork et al., brief for the United States as amicus curiae in Gregg v. Georgia, Landmark Briefs and Arguments of the Supreme Court of the United States, edd. Philip B. Kurland and Gerhard Casper (Washington, D.C.: University Publications of America, 1977), v. 90, pp. 293-296, 332-339; Peter Howe, “Death penalty bill raises issue of effect,” The Boston Globe, Dec. 2, 1991, p. 13; George D. Brower, “Death penalty: More effective arguments needed to reverse policy,” The Harrisburg Patriot, March 27, 1991, p. A7.; Richard Willing, “Death penalty gains unlikely defenders; Professors speak out in support of executions,” USA Today, Jan. 7, 2003, p. 1A; Cloninger and Marchesini, “Execution moratorium is no holiday for homicides,” www.prodeathpenalty.com/Moratoriums.htm; Dezhbakhsh, Rubin and Shepherd, “Does Capital Punishment Have a Deterrent Effect? New Evidence from Postmoratorium Panel Data,” American Law and Economics Review V5 N2 2003 (344-376); Mocan and Gittings, econ.cudenver.edu/home/workingpapers/2001_18.pdf

Other researchers have done their best to cast doubt on deterrence, and it’s clear that executions, however numerous, could never deter every murder. But experience just as clearly belies the dogmatic assertion, so cherished by liberals, that executions deter no one at all. It seems obvious that some murders are deterrable, and their victims’ lives are thrown away when capital punishment is not enforced.

As long as death for murder is an extreme rarity, however, any deterrent effect will be hard to detect. And if it ever is to be visible to the naked eye, it ought to show up first in Texas, the state that in recent years has become notorious as having by far the busiest death row in America.

During the nationwide moratorium on capital punishment that lasted from mid-1967 until late 1977, the murder rate rose sharply, but it varied widely from state to state. Local socioeconomic and cultural factors must account for the variation, for with regard to executions all states were equal. That, however, would soon change. After the execution hiatus came to an end, Texas, like the rest of the nation, was slow to resume capital punishment. Late in 1982, it carried out one execution, one of only two that year nationwide. In that year, 2,466 Texans died at murderers’ hands. The state’s per-capita murder rate was 16.1 per 100,000 inhabitants, far higher than 1982’s national rate of 9.1. By the mid-’90s, the annual number of executions in Texas had risen into double digits. In 2000, murderers killed 1,236 Texans, and Texas carried out a record 40 executions, accounting for almost half of the 85 carried out nationwide that year.

Between 1982 and 2002, the nation’s murder rate fell 38 percent. Texas — despised by “progressives” as the execution capital of the nation — beat that trend by a little bit, with its murder rate falling 63 percent, to 6.0 per 100,000, scarcely over 2002’s national rate of 5.6. This is even more striking when compared to the jurisdictions — 12 states and the District of Columbia — that have no death penalty. Their murder rate fell only 21 percent.

Rates are calculated using data from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports, the Texas Department of Public Safety’s Crime Information Bureau, and the Death Penalty Information Center. See also Judge Paul Cassell’s discussion of deterrence in Debating the Death Penalty: Should America Have Capital Punishment? The Experts from Both Sides Make Their Case (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), pp. 189-197.

During his televised debates with Al Gore in 2000, then-Texas Gov. George W. Bush was challenged on his state’s use of the death penalty. “I believe it saves lives,” Bush replied, and the evidence certainly appears to bear him out. ——— www.debates.org/pages/trans2000c.html [back]

[24] Schlosser, “A Grief Like No Other,” Atlantic Monthly, September 1997, pp. 37-76. [back]

[25] Wilson, “Thinking About Crime: The Debate Over Deterrence,” The Atlantic Monthly, September 1983, p. 88. [back]

[26] Sterling, op.cit., pp. 191-193. [back]

[27] Rogers, There’s Not a Bathing Suit in Russia (New York: Albert & Charles Boni, 1927), pp. 150-155. Rogers visited the Soviet Union again during a round-the-world tour in 1935 and “was shocked by what he saw of the Russians. The lot of the women, especially, bothered him. In order to eat they ‘had to live under the most degrading circumstances,’ and the suicide rate was the highest in the world. He found the Reds ‘a mighty hard looking lot.’ “ ———Ketchum, op. cit., pp. 204, 344-345. [back]

[28] Legal scholar George Goldberg comments: “In the beginning, there was no tension between the ‘establishment’ clause and the ‘free exercise’ clause [of the First Amendment]. … No one expected the federal government to be hostile to religion. In its own proper sphere, where its own affairs were concerned, it was naturally assumed that the federal government would maintain friendly relations with the various faiths represented by its members. Thus the first Congress, which proposed the Bill of Rights, appointed chaplains at the outset of its first session. It also appointed chaplains for the armed forces and resolved that George Washington’s inaugural should culminate in a divine service at St. Paul’s chapel, an Anglican church. Indeed, on the very day that it approved the First Amendment Congress called upon President Washington to proclaim a day of ‘public thanksgiving and prayer.’ Sessions of the United States Supreme Court were, as they still are, commenced with a prayer that ‘God save the United States and this honorable Court.’ “ ——— Goldberg, Reconsecrating America (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1984), pp. 1-4.

If arrangements such as these are consistent with the First Amendment as the Framers understood it, what would an actual "establishment of religion” consist of? Contemporary practices and documents such as Thomas Jefferson’s “Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom” make clear that it involves compulsory church attendance, government collection of tithes, legal penalties for heresy, and religious tests for the rights of citizenship. Jefferson’s bill provided that “no man shall be compelled to frequent or support any religious worship, place, or ministry whatsoever, nor shall be enforced, restrained, molested, or burthened in his body or goods, nor shall otherwise suffer, on account of his religious opinions or belief; but that all men shall be free to profess, and by argument to maintain, their opinions in matters of religion, and that the same shall in no wise diminish, enlarge, or affect their civil capacities.” Those principles do not constitute a ban against any public, official acknowledgment of God. So far were they from being understood as such, they were prefaced by Jefferson himself with this official pronouncement, contained in Section I of the bill, which declares “that Almighty God hath created the mind free, and manifested his supreme will that free it shall remain by making it altogether insusceptible of restraint; that all attempts to influence it by temporal punishments, or burthens, or by civil incapacitations, tend only to beget habits of hypocrisy and meanness, and are a departure from the plan of the holy author of our religion, who being lord both of body and mind, yet chose not to propagate it by coercions on either, as was in his Almighty power to do, but to extend it by its influence on reason alone.” Imagine the apoplexy on the Left if the words “Almighty God,” “his supreme will” and “the holy author of our religion” were to appear in a piece of legislation today! ——— Jefferson, Writings (New York: Library of America, 1984), pp. 346-347). [back]

[29] Letter to the Officers of the First Brigade of the Third Division of the Militia of Massachusetts (October 11, 1798). The Works of John Adams, Second President of the United States; With A Life of the Author Notes and Illustrations of his Grandson Charles Francis Adams, Vol. IX, Books For Libraries Press, Freeport, New York, (First Published 1850-1856, Reprinted 1969), 228-29. [back]

[30] The Living Thoughts of Thomas Jefferson, ed. John Dewey (New York: Fawcett, 1940), pp. 103-105. [back]

[31] In speeches,

articles, books and letters written both as a sitting and a former president, TR

preached this gospel: “There is no patent recipe for getting good citizenship. You

get it by applying the old, old rules of decent conduct, the rules in accordance

with which decent men have had to shape their lives from the beginning …

fundamental precepts, put forth in the Bible and embodied consciously or

unconsciously in the code of morals of every great and successful nation from

antiquity to modern times. … You are not going to make any new commandments at

this stage which will supply the place of the old ones. The truths that were

true at the foot of Mt. Sinai are true now. The truths that were true when the

Golden Rule was promulgated are true now. No man is a good citizen unless he so

acts as to show that he actually uses the Ten Commandments, and translates the

Golden Rule into his life conduct. I appeal for a study of the Bible on many

different accounts, even aside from its ethical and moral teachings, even aside

from the fact that all serious people, all men who think deeply, even among

non-Christians, have come to agree that the life of Christ, as set forth in the

four Gospels, represents an infinitely higher and purer morality than is

preached in any other book of the world. … The teachings of the Bible are so

interwoven and entwined with our whole civic and social life that it would be

literally — I do not mean figuratively, I mean literally — impossible for us to

figure to ourselves what that life would be if these teachings were removed. We

would lose almost all the standards by which we now judge both public and

private morals; all the standards toward which we, with more or less resolution,

strive to raise ourselves.” ——— Nathan Miller, Theodore Roosevelt: A Life

(New York: William Morrow, 1992), p. 198; Theodore Roosevelt, The Free

Citizen: A Summons to Service of the Democratic Ideal, ed. Hermann Hagedorn

(New York: Macmillan, 1956), pp. 25-30.

[back]

[31] In speeches,

articles, books and letters written both as a sitting and a former president, TR

preached this gospel: “There is no patent recipe for getting good citizenship. You

get it by applying the old, old rules of decent conduct, the rules in accordance

with which decent men have had to shape their lives from the beginning …

fundamental precepts, put forth in the Bible and embodied consciously or

unconsciously in the code of morals of every great and successful nation from

antiquity to modern times. … You are not going to make any new commandments at

this stage which will supply the place of the old ones. The truths that were

true at the foot of Mt. Sinai are true now. The truths that were true when the

Golden Rule was promulgated are true now. No man is a good citizen unless he so

acts as to show that he actually uses the Ten Commandments, and translates the

Golden Rule into his life conduct. I appeal for a study of the Bible on many

different accounts, even aside from its ethical and moral teachings, even aside

from the fact that all serious people, all men who think deeply, even among

non-Christians, have come to agree that the life of Christ, as set forth in the

four Gospels, represents an infinitely higher and purer morality than is

preached in any other book of the world. … The teachings of the Bible are so

interwoven and entwined with our whole civic and social life that it would be

literally — I do not mean figuratively, I mean literally — impossible for us to

figure to ourselves what that life would be if these teachings were removed. We

would lose almost all the standards by which we now judge both public and

private morals; all the standards toward which we, with more or less resolution,

strive to raise ourselves.” ——— Nathan Miller, Theodore Roosevelt: A Life

(New York: William Morrow, 1992), p. 198; Theodore Roosevelt, The Free

Citizen: A Summons to Service of the Democratic Ideal, ed. Hermann Hagedorn

(New York: Macmillan, 1956), pp. 25-30.

[back]

[32] In a 1950

speech at Gonzaga University, President Truman based both his foreign policy

(anti-Communism) and his domestic policy (civil rights) on religious and moral

values: “Men can build a good society, if they follow the will of the Lord. Our

great Nation was founded on this faith. Our Constitution, and all our finest

traditions, rest on a moral basis. We believe in the dignity and the rights of

each individual. We believe that no person — and no group of people — has an

inherent right to rule over any other person or any other group. … We are

continuing to move forward every day toward greater freedom and equal

opportunity for all citizens. This is a purpose each of us must strive to

achieve, in his daily life, and in his own community. It is a purpose which, in

some cases, requires collective action, through our elected representatives in

local, State, and Federal governments. … Nations can live together peacefully,

working for their common welfare, just as we do in this country. If they believe

in the brotherhood of man, under God, millions and millions of people, all over

the world, know in their hearts we can live together. … The greatest

obstacle to peace is a modern tyranny led by a small group who have abandoned

their faith in God. These tyrants have forsaken ethical and moral beliefs. They

believe that only force makes right. They are aggressively seeking to expand the

area of their domination. Our effort to resist and overcome this tyranny is

essentially a moral effort. Those of us who believe in God, and who are

fortunate enough to live under conditions where we can practice our faith,

cannot be content to live for ourselves alone, in selfish isolation. We must

work constantly to wipe out injustice and inequality, and to create a world

order consistent with the faith that governs us. … In the face of aggressive

tyranny, the economic, political, and military strength of free men is a

necessity. But we are not increasing our strength just for strength’s sake. … It

is the moral and religious beliefs of mankind which alone give our strength

meaning and purpose.” ———

http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1455

[32] In a 1950

speech at Gonzaga University, President Truman based both his foreign policy

(anti-Communism) and his domestic policy (civil rights) on religious and moral

values: “Men can build a good society, if they follow the will of the Lord. Our

great Nation was founded on this faith. Our Constitution, and all our finest

traditions, rest on a moral basis. We believe in the dignity and the rights of

each individual. We believe that no person — and no group of people — has an

inherent right to rule over any other person or any other group. … We are

continuing to move forward every day toward greater freedom and equal

opportunity for all citizens. This is a purpose each of us must strive to

achieve, in his daily life, and in his own community. It is a purpose which, in

some cases, requires collective action, through our elected representatives in

local, State, and Federal governments. … Nations can live together peacefully,

working for their common welfare, just as we do in this country. If they believe

in the brotherhood of man, under God, millions and millions of people, all over

the world, know in their hearts we can live together. … The greatest

obstacle to peace is a modern tyranny led by a small group who have abandoned

their faith in God. These tyrants have forsaken ethical and moral beliefs. They

believe that only force makes right. They are aggressively seeking to expand the

area of their domination. Our effort to resist and overcome this tyranny is

essentially a moral effort. Those of us who believe in God, and who are

fortunate enough to live under conditions where we can practice our faith,

cannot be content to live for ourselves alone, in selfish isolation. We must

work constantly to wipe out injustice and inequality, and to create a world

order consistent with the faith that governs us. … In the face of aggressive

tyranny, the economic, political, and military strength of free men is a

necessity. But we are not increasing our strength just for strength’s sake. … It

is the moral and religious beliefs of mankind which alone give our strength

meaning and purpose.” ———

http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1455

Historian Elisabeth Edwards Spalding comments: “At the time, various religious leaders and journals of the Truman era — notably, the Christian Century — consistently criticized what they viewed as the president’s simplistic religious exhortations on complex issues. But Truman believed … the threat from international communism could be best solved if free men were to use their intelligence, courage, and faith and to seek solutions in the spirit of the Sermon on the Mount. He invoked a consistent theme of his life and presidency: that all, especially but not only Christians, could understand, accept, and act on the message of Jesus’ Beatitudes and golden rule.” ——— Spalding, The First Cold Warrior: Harry Truman, Containment, And the Remaking of Liberal Internationalism (Lexington, Ky.: University Press of Kentucky, 2006), p. 213. [back]

[33] George

Washington in his Farewell Address wrote: “The basis of our political systems is

the right of the people to make and to alter their constitutions of government.

But the Constitution which at any time exists, till changed by an explicit and

authentic act of the whole people, is sacredly obligatory upon all. … If in the

opinion of the people, the distribution or modification of the constitutional

powers be in any particular wrong, let it be corrected by an amendment in the

way in which the Constitution designates. But let there be no change by

usurpation; for though this, in one instance, may be the instrument of good, it

is the customary weapon by which free governments are destroyed. The precedent

must always greatly overbalance in permanent evil any partial or transient

benefit which the use can at any time yield.” James Madison wrote: “I entirely

concur in the propriety of resorting to the sense in which the Constitution was

accepted and ratified by the nation. In that sense alone it is the legitimate

Constitution. And if that be not the guide in expounding it, there can be no

security for a consistent and stable, more than for a faithful, exercise of its

powers.” And: “A regular mode of making proper alterations has been providently

inserted in the Constitution itself. It is anxiously to be wished, therefore,

that no innovations may take place in other modes, one of which would be a

constructive assumption of powers never meant to be granted. If the powers be

deficient, the legitimate source of additional ones is always open, and ought to

be resorted to.” And: “I cannot but highly approve the industry with which you

have searched for a key to the sense of the Constitution, where alone the true

one can be found: in the proceedings of the Convention, the contemporary

expositions, and above all in the ratifying Conventions of the States. If the

instrument be interpreted by criticisms which lose sight of the intention of the

parties to it, in the fascinating pursuit of objects of public advantage or conveniency, the purest motives can be no security against innovations

materially changing the features of the Government.” ——— Madison, Writings

(New York, 1910), v. 8, pp. 447-453, v. 9, p. 191; Letters and Other Writings

of James Madison (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1865), v. 3, pp. 521-522.

[33] George

Washington in his Farewell Address wrote: “The basis of our political systems is

the right of the people to make and to alter their constitutions of government.

But the Constitution which at any time exists, till changed by an explicit and

authentic act of the whole people, is sacredly obligatory upon all. … If in the

opinion of the people, the distribution or modification of the constitutional

powers be in any particular wrong, let it be corrected by an amendment in the

way in which the Constitution designates. But let there be no change by

usurpation; for though this, in one instance, may be the instrument of good, it

is the customary weapon by which free governments are destroyed. The precedent

must always greatly overbalance in permanent evil any partial or transient

benefit which the use can at any time yield.” James Madison wrote: “I entirely

concur in the propriety of resorting to the sense in which the Constitution was

accepted and ratified by the nation. In that sense alone it is the legitimate

Constitution. And if that be not the guide in expounding it, there can be no

security for a consistent and stable, more than for a faithful, exercise of its

powers.” And: “A regular mode of making proper alterations has been providently

inserted in the Constitution itself. It is anxiously to be wished, therefore,

that no innovations may take place in other modes, one of which would be a

constructive assumption of powers never meant to be granted. If the powers be

deficient, the legitimate source of additional ones is always open, and ought to

be resorted to.” And: “I cannot but highly approve the industry with which you

have searched for a key to the sense of the Constitution, where alone the true

one can be found: in the proceedings of the Convention, the contemporary

expositions, and above all in the ratifying Conventions of the States. If the

instrument be interpreted by criticisms which lose sight of the intention of the

parties to it, in the fascinating pursuit of objects of public advantage or conveniency, the purest motives can be no security against innovations

materially changing the features of the Government.” ——— Madison, Writings

(New York, 1910), v. 8, pp. 447-453, v. 9, p. 191; Letters and Other Writings

of James Madison (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1865), v. 3, pp. 521-522.

This view of the matter was regarded, historian Johnathan O’Neill, says, “as axiomatic in a regime based on popular sovereignty.” Although on certain points disagreements arose as to what the Constitution’s original meaning was, no one in such disputes asserted that judges were free to disregard that meaning and substitute new concepts of their own creation. To do so, wrote Associate Justice Joseph Story, would amount to “the establishment of a new Constitution. It is doing for the people what they have not chosen to do for themselves. It is usurping the functions of a legislator.” ——— O’Neill, Originalism in American Law and Politics: A Constitutional History (Baltimore, Md: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005), pp. 12-17; Story, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States, 5th ed., 1905, v. 1, pp.325-326, quoted in Raoul Berger, Government By Judiciary: The Transformation of the Fourteenth Amendment, Second Edition (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1997), pp. 402-403. [back]

[34] In The Federalist No. 81, Alexander Hamilton wrote: “The supposed danger of judiciary encroachments on the legislative authority, which has been upon many occasions reiterated, is in reality a phantom. Particular misconstructions and contraventions of the legislature may now and then happen; but they can never be so extensive as to amount to an inconvenience, or in any sensible degree to affect the order of the political system. … [This] inference is greatly fortified by the consideration of the important constitutional check, which the power of instituting impeachments, in one part of the legislative body, and of determining them in the other, would give to that body upon the members of the judicial department. This is alone a complete security. There never can be danger that the judges, by a series of deliberate usurpations on the authority of the legislature, would hazard the united resentment of [Congress], while this body was possessed of the means of punishing their presumption by degrading them from their stations.” [back]